Dinka and Nuer: Cousins Bound by Blood, History, and Destiny

In South Sudan’s long and painful history, few narratives have been as politically weaponized—and as deeply misunderstood—as the relationship between the Dinka and the Nuer. Often portrayed as eternal rivals, these two communities are, in truth, cousins bound by blood, shared ancestry, culture, and a common historical journey along the Nile basin. The tragedy of South Sudan is not that Dinka and Nuer are enemies by nature, but that politics and power struggles have repeatedly turned cousins against one another.

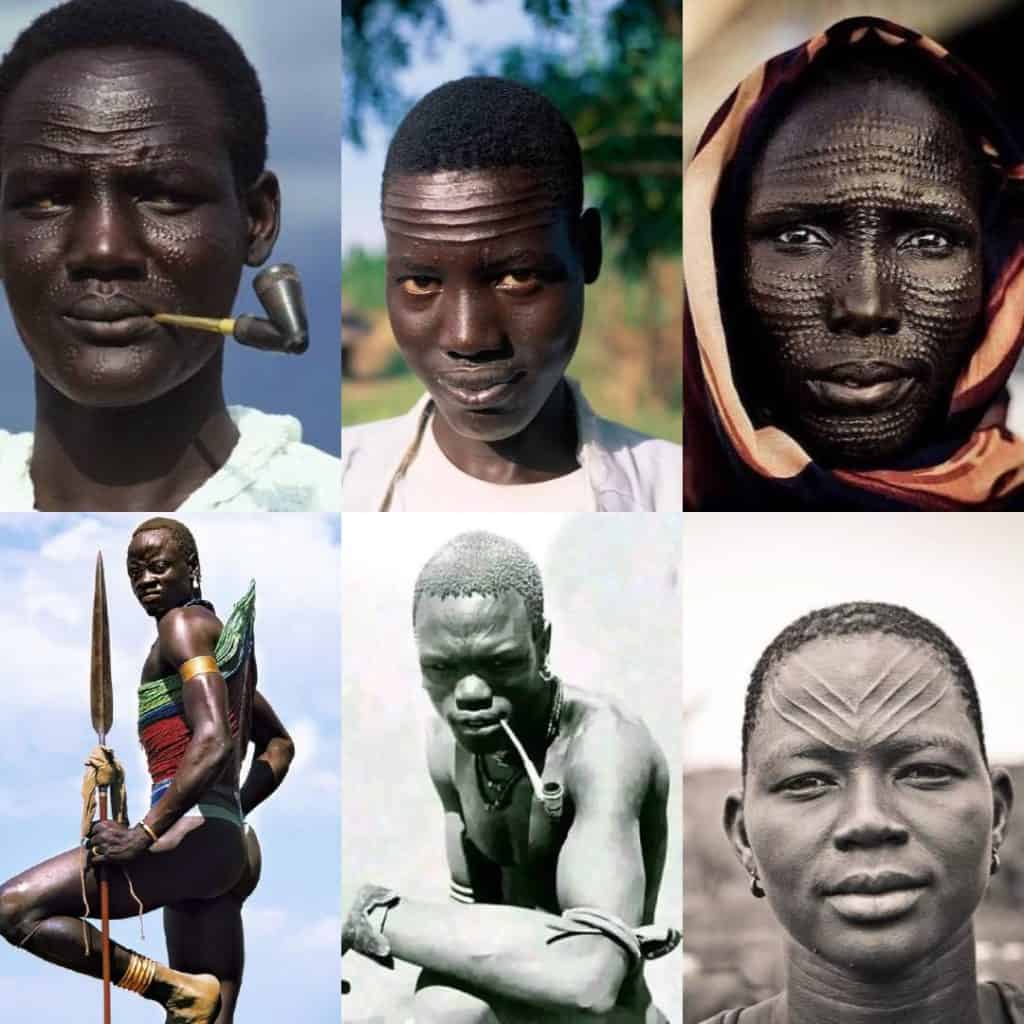

Anthropological, historical, and oral traditions consistently affirm that the Dinka and the Nuer originate from closely related Nilotic roots. They share linguistic similarities, social structures, spiritual beliefs, and pastoralist livelihoods centered on cattle. In many ways, the differences between them are no greater than those found among clans within the same ethnic group. Their languages are mutually intelligible to a significant degree, their customs around marriage, age-sets, and conflict resolution are strikingly similar, and their reverence for cattle as a source of identity, wealth, and social order is virtually identical.

Historically, the Dinka and Nuer lived side by side, intermarried, traded cattle, shared grazing lands, and even adopted each other’s clans through processes of assimilation and kinship. It was common for Nuer families to be absorbed into Dinka communities and vice versa, creating overlapping identities that defy today’s rigid ethnic labels. These interactions produced bonds of cousinhood—relationships rooted not only in bloodlines but in shared survival and coexistence.

The idea that Dinka and Nuer are destined to fight is a modern political construction rather than a historical reality. Pre-colonial conflicts between the two were largely localized, seasonal, and governed by traditional rules meant to limit destruction and preserve future coexistence. Elders mediated disputes, compensation replaced revenge, and reconciliation rituals restored harmony. War was never about extermination; it was about balance.

Colonial administration disrupted this equilibrium. The British policy of indirect rule hardened ethnic boundaries that were once fluid. Communities that had long interacted organically were suddenly categorized, separated, and governed as distinct “tribes.” This artificial division laid the groundwork for future political manipulation.

After independence, successive South Sudanese political elites further deepened the divide. Power struggles within liberation movements, especially during and after the SPLM/A era, were reframed along ethnic lines. Political disagreements between leaders were transformed into communal hostilities, with ordinary Dinka and Nuer civilians paying the highest price. Cousins were mobilized against cousins in wars they neither started nor benefited from.

The civil wars that erupted after 2013 stand as the clearest example of how elite rivalries can fracture social bonds. Political leaders invoked ethnic identity to consolidate power, recruit fighters, and silence dissent. In doing so, they weaponized fear and resurrected grievances, erasing generations of shared history. Yet even amid the violence, countless stories emerged of Dinka families sheltering Nuer neighbors, and Nuer communities protecting Dinka civilians—quiet acts of cousinhood resisting political madness.

It is crucial to state this plainly: Dinka and Nuer do not benefit from hating each other. Poverty, displacement, underdevelopment, and trauma afflict both communities equally. While politicians trade accusations and mobilize ethnic loyalties, ordinary people struggle for food, education, healthcare, and peace. The blood spilled in the name of ethnic supremacy has enriched no community—it has only strengthened the grip of failed leadership.

Rebuilding South Sudan requires reclaiming the truth of Dinka–Nuer relations. Cousins fight, yes—but cousins also reconcile. In traditional societies, cousinhood implies obligation, restraint, and eventual forgiveness. It means disputes must end, because blood cannot be erased. This cultural wisdom offers a powerful foundation for national healing if leaders are courageous enough to embrace it.

The future of South Sudan depends on unity rooted in truth, not slogans. Dinka and Nuer are not enemies by destiny; they are relatives divided by politics. Recognizing this reality does not deny past atrocities or genuine grievances—it contextualizes them and points toward a different path.

If South Sudan is to survive as a nation, its people must reject narratives that profit from division and instead revive those that honor shared origins. Cousins can disagree, compete, and even clash—but they must ultimately sit together, speak honestly, and rebuild what has been broken.

The blood that binds Dinka and Nuer is thicker than the lies that divide them.

Opinions expressed in articles published by RSSVP are those of the individual authors and do not necessarily represent the views of Rescue South Sudan Village People. RSSVP assumes no responsibility for the accuracy, validity, or reliability of claims made by contributors.

Author Bio

Abraham Madit Majak is a South Sudanese writer and political commentator with a strong focus on governance, peace processes, and civic accountability. He regularly contributes to public discourse on South Sudan’s political transition, the role of state institutions, and the responsibilities of leadership during critical reform and nation-building periods.